Adventures in Greenland - Part 2

Chasing Robert Peary’s Hallucinations

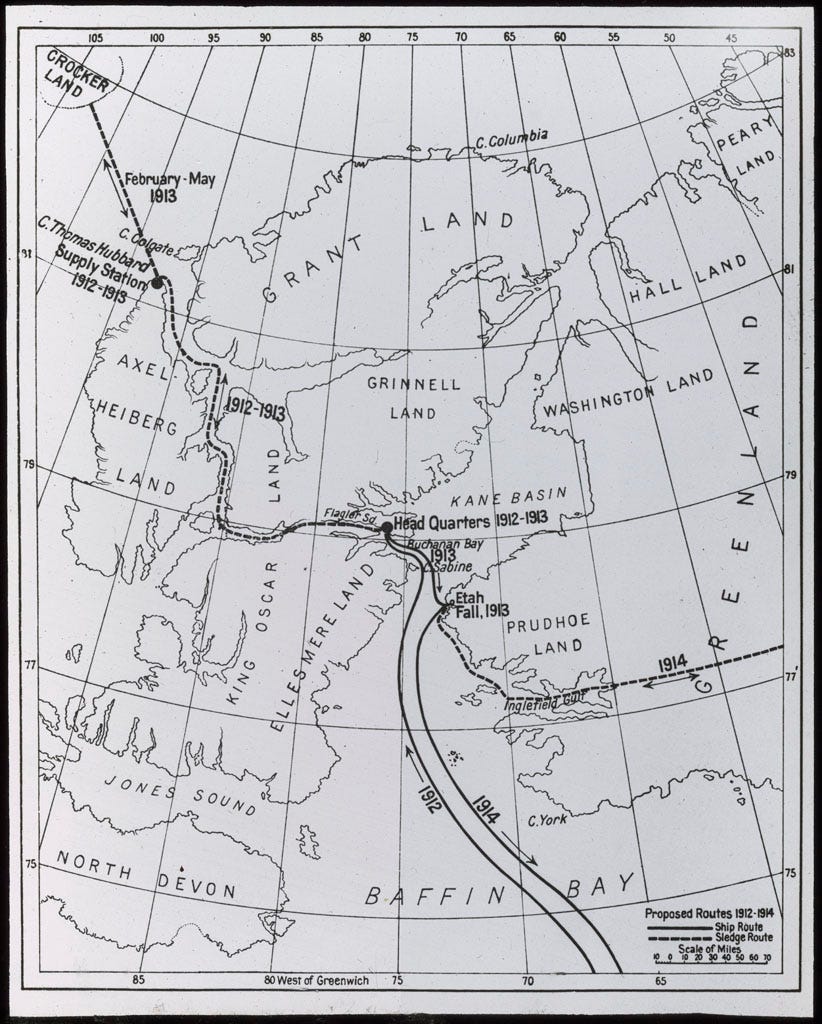

On 21st April 2013, a 39 year old American explorer, Donald McMillan, finally found the fabled Crocker Land, long rumoured to exist far north of Greenland. It had first been sighted by Robert Peary on his failed North Pole expedition of 1906. Unfortunately for McMillan, the islands that seemed only a few days travel away, did not exist.

McMillan’s, initally large, group of explorers had been reduced to only 4 men at this point. Two Americans and two Inuit guides. One of these, Piugaattoq, insisted that McMillan was looking at a poo-jok, or mirage. These are not uncommon in the Arctic, and in 1818 had caused John Ross to completely abandon an expedition to discover the Northwest Passage, assuming that mountains blocked his way. A year later, his first mate, William Parry, now with his own ship, proved Ross wrong by sailing ‘through’ these mountains.

McMillan was not easily deterred, and pushed on for another 5 days, covering 125 miles. Land never came any closer though, and he finally admitted defeat. He wrote in his diary:

”The day was exceptionally clear, not a cloud or trace of mist; if land could be seen, now was our time. Yes, there it was! It could even be seen without a glass, extending from southwest true to north-northeast. Our powerful glasses, however, brought out more clearly the dark background in contrast with the white, the whole resembling hills, valleys and snow-capped peaks to such a degree that, had we not been out on the frozen sea for 150 miles, we would have staked our lives upon its reality. Our judgment then, as now, is that this was a mirage or loom of the sea ice.”1

The four men now had to make the nearly 2,000km return journey across dangerous sea ice, back to Etah on the north west coast of Greenland. Not all would arrive back.

Despite the long journey ahead, and the warm weather making the ice increasingly dangerous, he decided to split the group, sending Piugaattoq and Green off to the west, with a plan to meet up a week later. The weather worsened, and for a while McMillan and Ittukusuk thought the others had been lost. Eventually Green appeared, minus Piugaattoq.

We only have Green’s word for what happened, but he changed his story a number of times. At first he claimed that Piugaattoq had set off with the dog sled, leaving him behind, and that he had shot him in order to save his own life. Later he said that Piugaattoq had been injured by an avalanche, and that it had been a ‘mercy’ killing, and later still, that there had been a fight, and that Piugaattoq had been armed. However, Green had been struggling physically, and the general conclusion was that he had murdered Piugaattoq. To add further intrigue, there were claims that Green had an affair with Aleqasina, Piugaattoq’s wife, although McMillan had a relationship with her as well, prior to this.

Green was never prosecuted, and returned to the US, where he was promoted. He served in the US Navy in both world wars and married twice. His life came to a somewhat ignominious end when he was arrested for dealing heroin in 1947. He had become an addict himself, and died in hospital a few months after his arrest.2

Upon his return to Etah, the small encampment in North West Greenland, he sent messages back to the US requesting a rescue. Two ships were sent, but never arrived due to ice. At this point, after waiting for two years for a ship, Maurice Tanquary, Fitzhugh Green, and J.L. Allen decided to travel overland to the South, to try and catch a ship back to the US.

Remarkably, they did manage this journey of 1,200 miles, the equivalent of going from Madrid to Berlin, mostly across the ice and sea. McMillan and the others were picked up a year later, rescued by arguably the only decent and undoubtedly heroic Arctic explorer, Robert Bartlett.3

Despite the chaos and disappointment of the Expedition, McMillan went on to have a remarkably successful career. He put together a dictionary of the Inuktitut language, produced Inuit films, took photographs of Arctic scenes, and made audio recordings of Inuit languages. He contributed to major studies of flora and fauna in Greenland, discovered possible Viking ruins in Labrador, supported his wife, Miriam, to become a major Inuit ethnographer, served in the Navy in his 60s during World War 2, and died at the age of 95 in 1970.

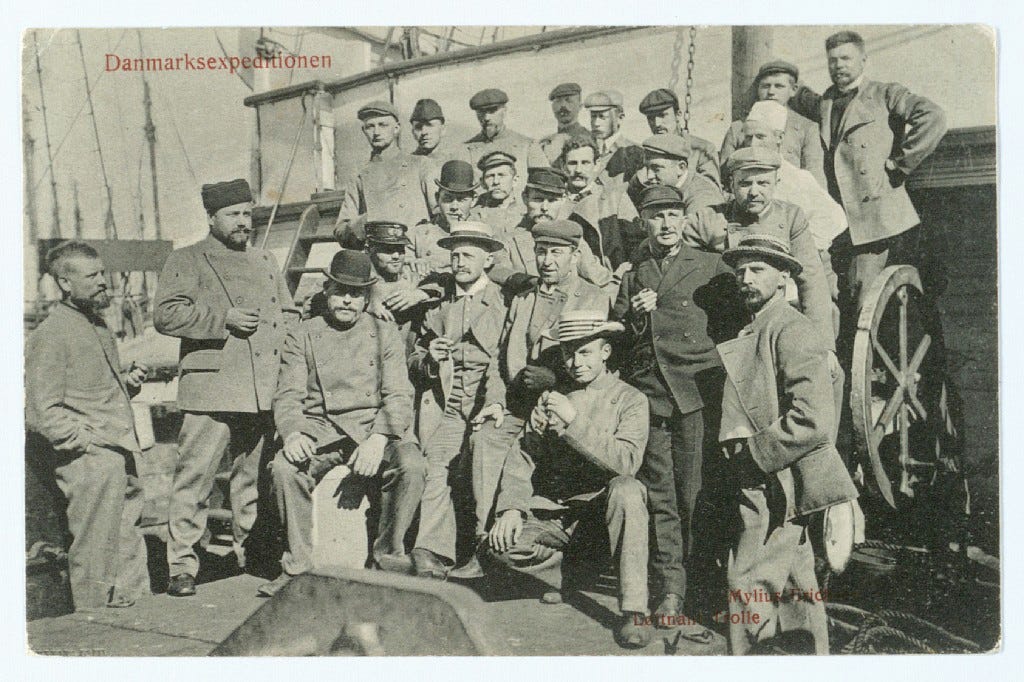

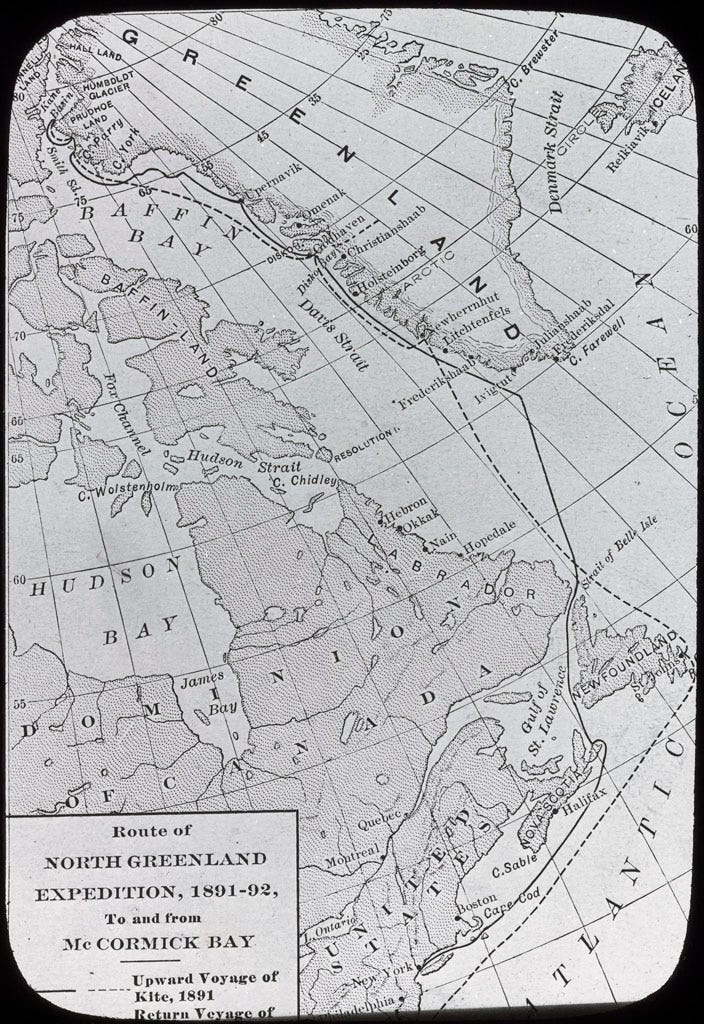

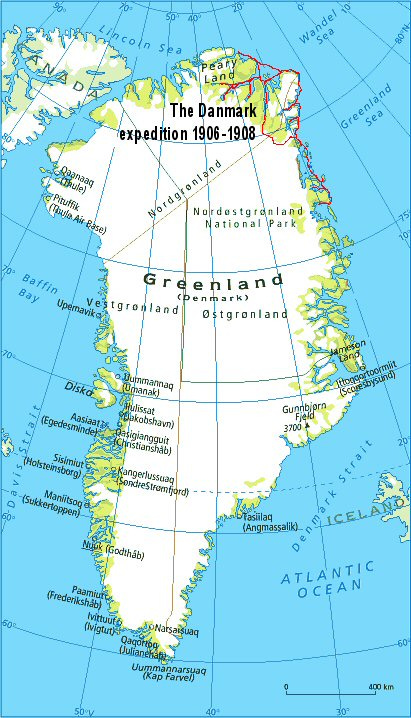

7 years earlier, in 1906, another group of explorers had set off to Greenland, this time to find the fabled Peary Channel. The Denmark Expedition aimed to map the last uncharted parts of Greenland, and the far north east, as well as carrying out various scientific endeavours.

This was Denmark’s largest expedition to date, with 28 men in total, hoping to map 1,000 miles of unknown Greenland coastline. They set up camp at Danmarkshavn, a bleak part of the north eastern coast, which remains a scientific station today.

From there, they split up into four groups, with around 80 sled dogs between them, and set off to the north, aiming to find a straight which Peary claimed seperated Greenland from an island further north.

Initially, all went well. The first support team returned after a few weeks with 2 dog sleds, then a second team turned back to give themselves time to map the East Coast and some off shore islands.

At this point things began to get more difficult. The expedition leader, Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen, was expecting to go West, but the coastline took them to the North East. You can see in the image below that they were rounding the peninsular named Crown Prince Christian Land:

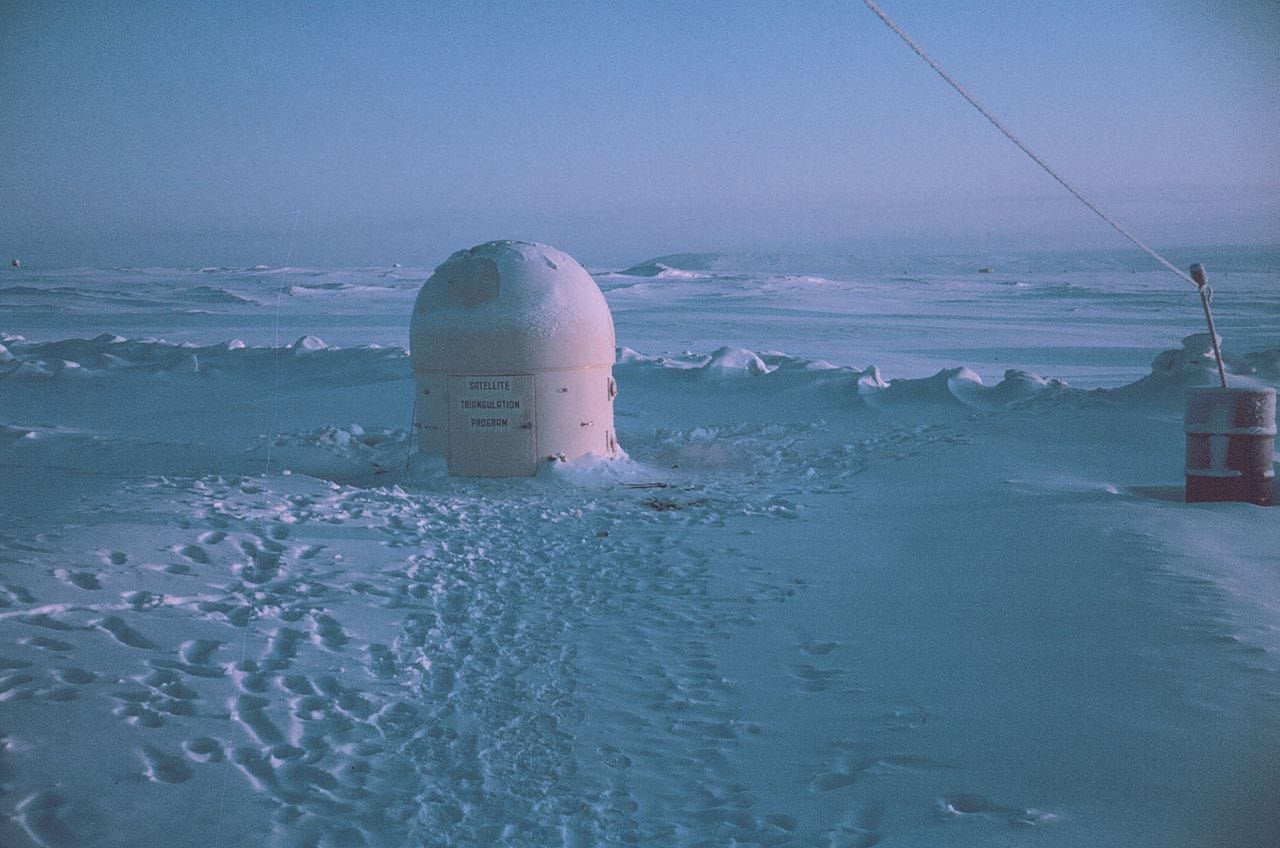

The extra time needed reduced their supplies, and hunting was difficult. They eventually rounded the peninsular, reaching a point where there is currently a scientific station named Station Nord. It’s an astonishingly bleak part of the world:

At this point Mylius-Erichsen split his team again, into two groups with three dog sleds each. The other team, led by Johan Peter Koch, went north west, hoping to map the eastern side of Peary Land, while Mylius-Erichsen took his team along the edge of Danmark Fjord, hoping to find the Peary Channel. Finding this to be a dead end, they retreated north, and, remarkably, managed to link up again with Koch’s team.

By this time they had been exploring for around 3 months, during the incredibly cold Greenland winter, but they didn’t have much time left. With the arrival of summer, the ice would break up, making travel across fjords impossible, and there would be very little to hunt. The obvious decision was to return to Danmarkshavn, and initially all agreed to do this, but for some reason, Mylius-Erichsen decided to take his small team further west. Koch’s men headed south, and reached Danmarkshavn a month later.

Mylius-Erichsen and his two colleagues went up Independence Fjord, a fateful decision, and again found it to be a dead end. Finally they knew that the Peary Channel was another figment of the imagination.

Below is an image of Independence Fjord. It’s vast, forbidding, and with broken ice, impassable for these men:

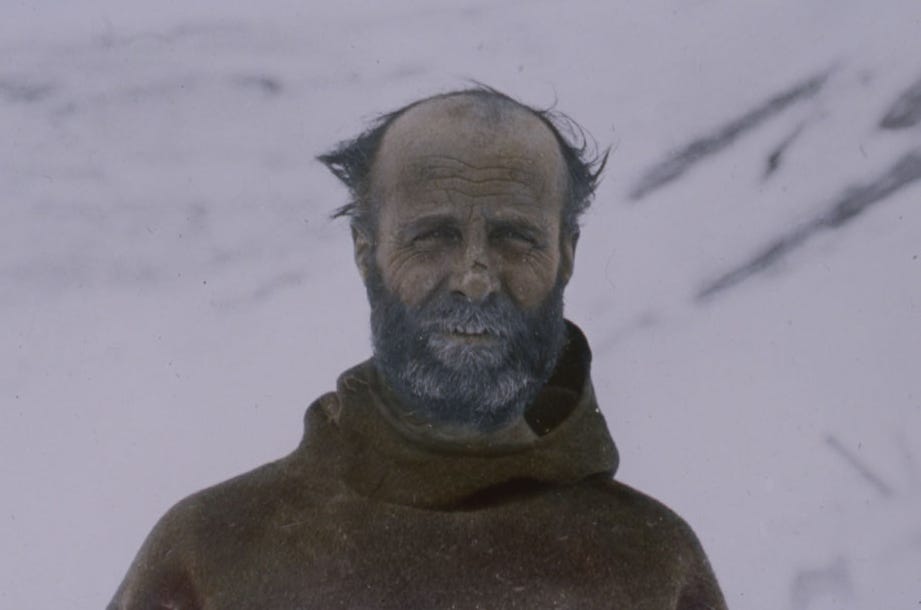

At this point they had to go inland to get around the many fjords blocking their way home, leaving them with a distance of 500 miles to trek. They tried to retreat along the initial route out, looking for depots of food which had been left behind. Høeg Hagen was the first to die, of exhaustion, in October 1907, after 6 months of travel. Soon after Mylius-Erichsen also collapsed.

Jørgen Brønlund managed to continue a little further, and by the time he died, he was only 140 miles from the relative safety of Danmarkshavn.

6 months later, in March 1908, Johan Peter Koch took out a team to find his missing colleagues, and remarkably, he found Brønlund’s body, along with all his notes and charts.

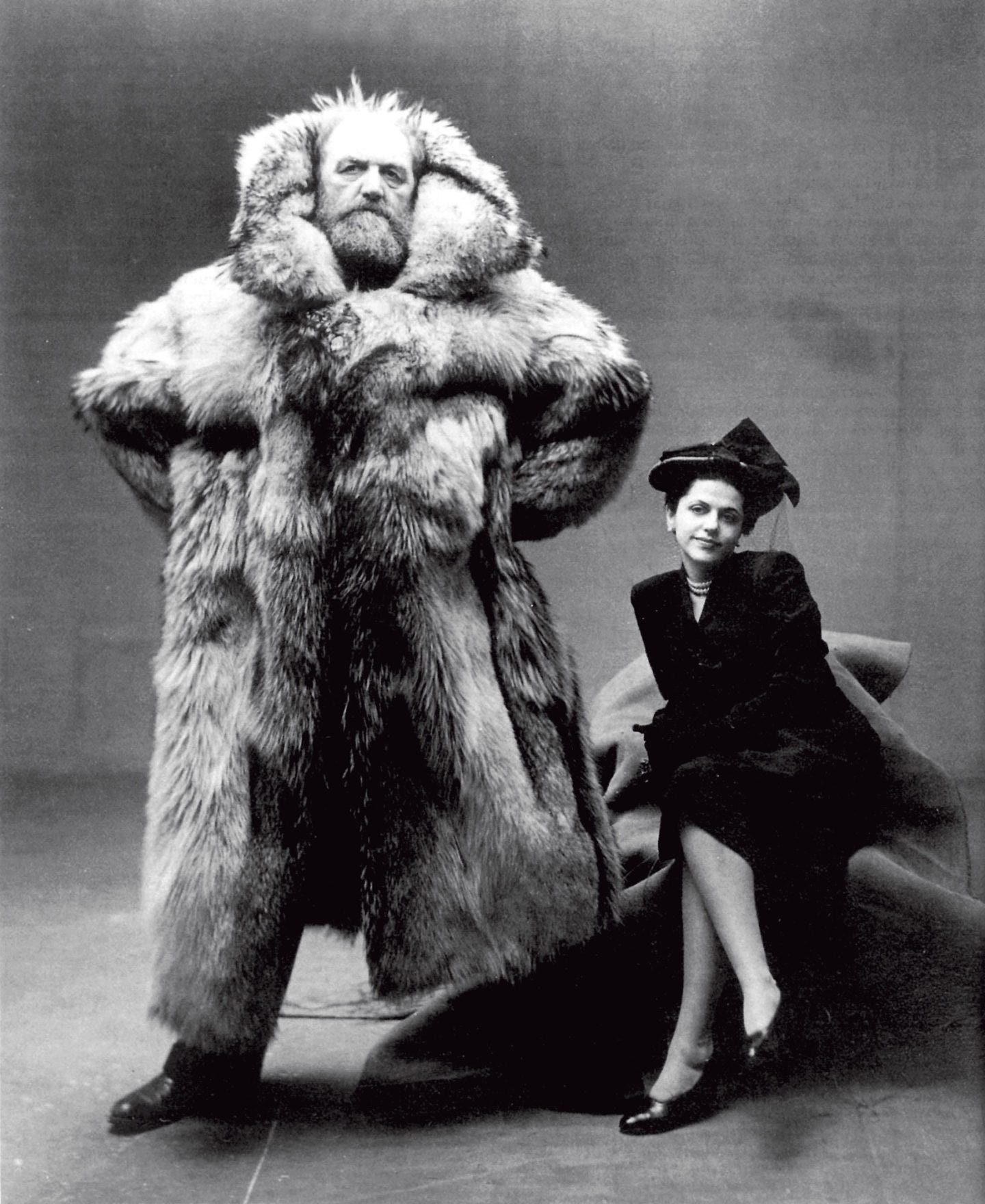

The death of these 3 men cast a pall over the Expedition, but in other ways it had been a success. 51 scientific reports were published, and many expedition members returned again and again to Greenland for further study. One team member, Peter Freuchen married an inuit lady, and posed years later for one of the most famous photos in history.

MacMillan, Donald Baxter; Ekblaw, Walter Elmer (1918). Four Years in the White North. Harper & Brothers. pp. 87–88.

https://www.nytimes.com/1947/12/03/archives/commander-green-dies-in-hospital-authorexplorer-durant-son-inlaw.html

Horwood, Harold (1977). Bartlett: The Great Canadian Explorer. Doubleday Canada. p. 116.

Really great article. Easy to read and fascinating tales of the explorers. Amazing photo!