Adventures in Greenland - Part 1

The Inuit who came to Europe

In the late 1600s, the inhabitants of Eda, one of the Orkney Islands, were surprised to see strangers arriving off the coast in small boats. “Sometime about this Country are seen these Men which are called Finnmen ; “In the year 1682, one was seen sometime sailing, sometime Rowing up and down in his little Boat at the south end of the Isle of Eda most of the people of the Isle flocked to see him, and when they adventured to put out a Boat with men to see if they could apprehend him, he presently fled away most swiftly”, wrote the Reverend James Wallace of Kirkwall, Orkney.1

The men they had encountered were clearly not the fishermen who and traders who travelled between Orkney, Scotland and the Netherlands, selling Herring. These people were Inuit, and they had completed one of the most remarkable journeys of discovery known to mankind.

The Maunder Minimum was a period of very cold weather, roughly between 1645 and 1715, and its impact was devastating. The 1680s and 1690s were especially wet and cold, and in 1695 there were severe famines in Scotland and Norway. Estonia and Finland lost 20% and 30% of their populations respectively. Ten years later, the entire poultry population of Northern France was wiped out.

Further north, this weather meant that Iceland was almost continuously surrounded by ice, and for Inuit in the far north, in places like Boothia Peninsular, Baffin Island and the Coronation Gulf, the only option was to flee south, resulting in conflict with other Inuit.

Eastern Greenland had always been a harsh environment in which to live, and the Vikings had made no attempt to settle there. Brutal winds blow down from the ice sheets, tall jagged mountains limit the arable land, and the constant sea ice makes it difficult to fish. During the freezing weather of the late 1600s, many Inuit became desperate, and set out in search of new land, in a reversal of the Viking journeys. They too had been desperate to find new land to sustain them following a change in climate.

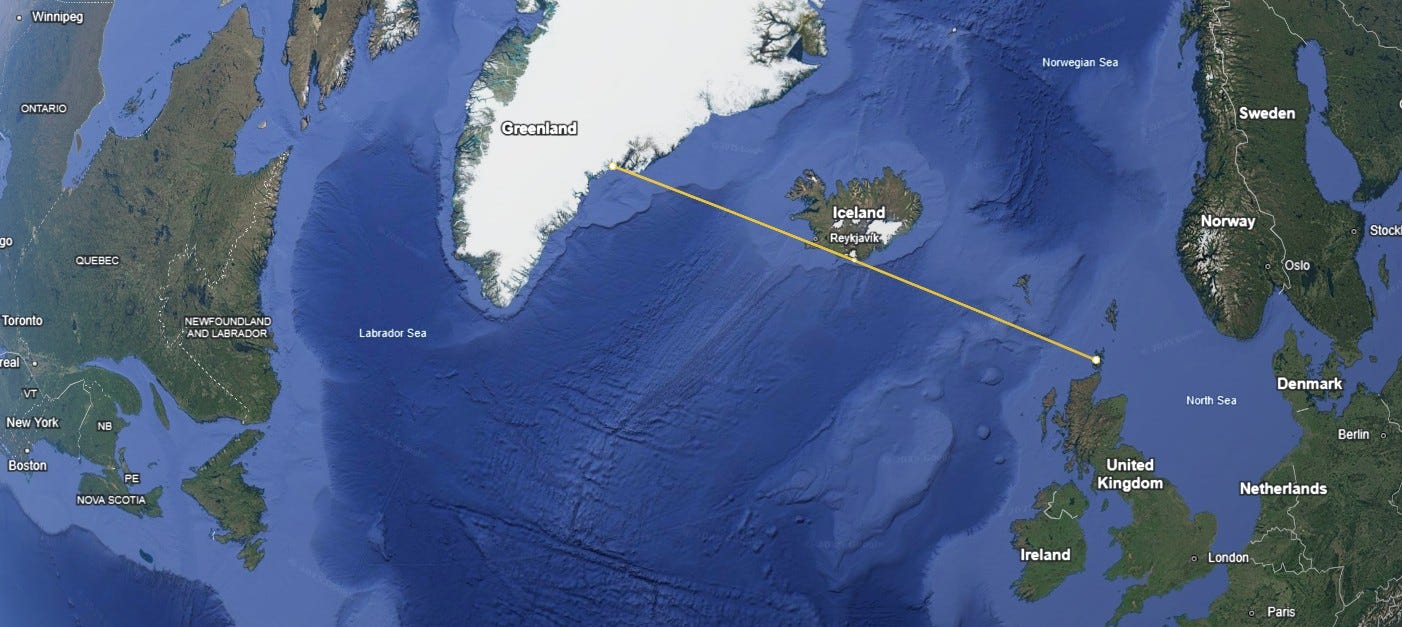

Later legends tell us that some Inuit set off from Ammassalik, and the journey from there, across the Strait of Denmark, and then the North Atlantic, is around 2,000km. In the 1850s, the Danish naturalist Hinrich Rink recorded these stories of Inuit travelling from Ammassalik out to Akilineq, a mysterious place somewhere in the West. He noted that they were not legends in the European sense, but rather were intended as fairly accurate accounts of real events. Rink was intrigued by one key detail, that those who had travelled there had seen houses with chimneys, which were unknown in Greenland, but did exist in Iceland.2

These stories tell of brothers who set out to find new lands. One after another they left, and three eventually stayed living in Akilineq. The fourth returned to Ammassalik to tell the fifth brother the story. To reach their destination, they had gone from one island to another, sailing past, or walking across the ice, which had reached deep into the Atlantic. Rink could have been forgiven for assuming these were fictional tales, but they fall into a special category of Inuit story, which is designed to contain true histories of real events. 3

Which brings us back to James Wallace, who recounts further contact with travelling Inuit; “And in the Year 1684, another was seen from Westra, and for a while after they got few or no Fishes ; for they have this Remark here, that these Finnmen drive away the fishes from the place to which they come”

Some have suggested that these were Inuit who had been brought to Europe by Europeans, and had escaped, but Wallace’s astonishingly detailed footnote show that was not the case; “I must acknowledge it seems a little unaccountable how these Finn-men should come on this coast, but they must probably be driven by storms from home, and cannot tell, when they are any way at sea, how to make their way home again ; they have this advantage, that be the Seas never so boisterous, their boats being made of Fish Skins, are so contrived that he can never sink, but is like a Sea-gull swimming on the top of the watter. His shirt he has is so fastned to the Boat, that no water can come into his Boat to do him damage, except when he pleases to untye it, which he never does but to ease nature, or when he comes ashore.”

Further evidence is found in Aberdeen Museum, where there is still a Kayak from 1760. In that year, the Rev. Francis Gastrell wrote in his diary; “A canoe about seven yards long by two feet wide, which about thirty-two years since was driven into the Don with a man in it who was all over hairy, and spoke a language which no person there could interpret. He lived but three days, although all possible care was taken to recover him.”4

For hundreds of years there has been understandable doubt about whether such a journey was possible, and so in 2016, two intrepid modern day explorers set off in a kayak from Greenland, aiming to pass Iceland, Orkney, and finally to reach Scotland. Their successful journey, demanding exceptional endurance and skill, confirms what Inuit oral histories had long suggested.5

Note: This article was deeply informed by Renée Fossett’s In Order to Live Untroubled, a superb history of the Central Artic Inuit.

James Wallace, Description of the Isles of Orkney (1693; repr. Edinburgh: William Brown, 1883), p. 28. Available at: https://archive.org/details/descriptionofisl00wall/page/28/mode/2up

Hinrich Rink, Tales and Traditions of the Eskimo (Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1875). Available at: https://archive.org/details/talestraditions00rinkuoft

Renée Fossett, In Order to Live Untroubled: Inuit of the Central Arctic, 1550 to 1940 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2001), p. 144

Rev. Francis Gastrell, Diary, 1760. Cited in Nature, vol. 107 (1921), p. 141

Really interesting and attractively written...should be on a podcast